Warming-Up

You may have had a gym teacher, coach, or personal trainer go on and on about the importance of a proper warm-up before a workout or race. But your time is precious- maybe you only have 45 minutes to get a workout in before you have to get back to the office. In order to make the most of our minutes in the gym, many of us tend to skip the warm-up and get right down to business. But without a proper warm-up, you could be setting yourself up for injury: studies have shown that some of the benefits of warming up are an increase in core temperature and circulation—both of which can help make tight muscles more pliable and make movement more efficient, thereby reducing the risk of injury. Anecdotal evidence suggests that warming up helps increase focus and mental preparedness. For instance, if you are about to perform a deadlift at a moderate to heavy weight for a low number of repetitions, warming up prior to deadlifting can help you ease into the movement, helping you to feel more comfortable and capable at a higher weight.

Warming up is a widely accepted and generally encouraged practice. But most generally active people have no idea what to do for a warm-up—so they typically end up not warming up at all. On top of that, how long does a warm up need to be in order to gain the benefits? And how do you know if you’re “warmed up” anyway?

During my time as a rower, a coach of mine had a saying: “don’t rush the warm-up.” Years later, this saying has taken on a few nuances that have changed how I treat warming up.

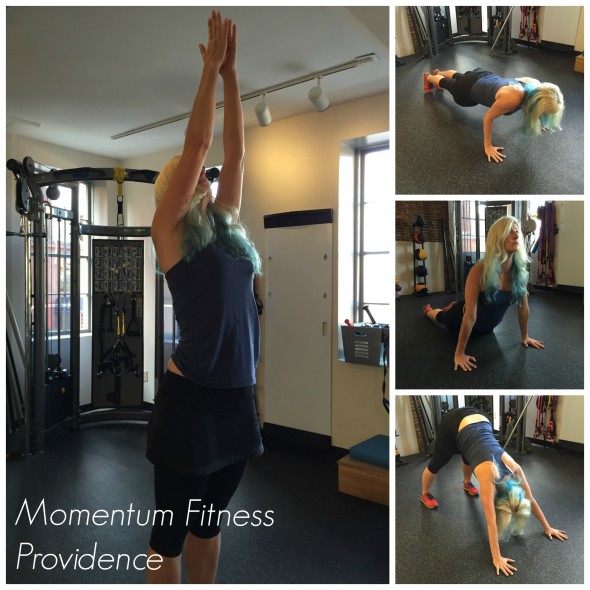

1.) Don’t rush the warm-up. Seriously. Take your time and keep the intensity relatively low to start. If you’re prepping for a 3 mile run or jog (which would take about 27 minutes for someone running at a 9 minute/mile pace), do not immediately hit the pavement and expect to hold top speed. Besides entirely defeating the purpose of a warm-up, you may find it difficult to reach and feel comfortable at a quick pace, particularly if you’ve been seated for most of the day. Giving yourself 5-7 minutes to do some dynamic stretching and walking or light jogging before your run will help increase the blood flow to the muscles that you’re about to use and prime them for more intense activity. Similarly, if you were going to bench press, doing exercises that mimic the bench press (such as a pushup) and a couple of light sets using controlled motion will serve you much better than jumping right to the weight you remember doing 5 reps with last week.

2.) Give yourself time to actually warm up (and, see #1, don’t rush it!) We’re all guilty of showing up to the gym for a workout or personal training session right on time, because life happens. But, if you’re like most Americans and spend most of your day at a desk, get to the gym with time to spare. While there isn’t much decisive research regarding how long a warm-up must be in order to be effective, most people agree on about ten minutes of light, movement specific activity—you should break a sweat, but you shouldn’t feel as though you’ve reached maximum exertion. Ten minutes is not a hard and fast rule, either, as some people may need more or less time to feel their core temperature rise, depending on factors such as age or outside temperature. If you can, ask your trainer about what he or she has programmed for your session so that you can do movements that are specific to the kinds of movements you will be training.

3.) Pay attention to how you’re feeling. That nagging hip/back/shoulder injury being especially annoying today? Feeling sluggish because you got three hours of sleep last night? Your warm-up can also function as your time to do a total body-scan to figure out how you feel once you get moving. Is the calf cramp you felt going downstairs this morning beginning to subside within the first few minutes of your warm-up? Good, but monitor it at your discretion. Does your shoulder bother you just doing a modified pushup, when you can normally do a dozen regular ones? You may need to alter your workout for the day or train around it. If you work with a trainer, a warm up is a good opportunity to gauge together how you are feeling, particularly if you have a lingering injury.

So, the next time you find yourself at the gym, or getting ready for a session with your trainer, don’t forget the warm up. You’ll move better, and your mind as well as your muscles will be prepared for the demands of whatever your workout entails.

-Maria Capuano, NASM Personal Trainer

The Most Important Exercise You May Not Be Doing

Wondering how you can lower your everyday stress level, be more focused, and even perform better on your workouts? The answer could be something you’re (hopefully) doing right now.

If you’re breathing now, you’re on the right track.

Fundamentally, breathing is how humans take in oxygen so that cells can then use the oxygen to make cellular energy. Without enough of that cellular energy (also known as ATP), we wouldn’t get very far in our daily activities. The more oxygen we are able to efficiently take in, the more balanced and energized we are able to feel (“Why Do We Breathe?” snow brains.com). Breathing deeply and purposefully can also seem to quiet a stressful mind because of a physiological response that recurs in the brain. When you feel overwhelmed, angry, or sad, the brain is cued to release certain hormones (these are released in times of a late night ice cream craving or chronic fatigue—and everything in between) that prepare the body to deal with those emotions. This is called the “fight or flight” response, a leftover characteristic of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Apparently evolutionarily, being chased by a wooly mammoth is not too different than speaking in public where our brain’s chemical response is concerned.

You’re probably wondering what physiology, hormones, wooly mammoths, and breathing all have to do with YOU, and what exactly does it mean to “breathe purposefully/mindfully. Take a second to do a self-assessment of your breathing. Make sure you are in a comfortable position, and rest one hand on your chest and the other over your belly button. Take a deep breath. Which rose first, your chest or your stomach?

If your chest rose first, you may be having some trouble activating the diaphragm, which is the cylindrical muscle usually associated with deep breathing and the belly expansion that comes along with it. Many people tend not to engage their diaphragm during regular, relaxed breathing because, hey, who wants to look like they have a belly when they’re just standing there, breathing? As a result, they tend to “chest breathe” (also known as apical breathing) relying on other muscles to get air into the lungs, which are only able to partially expand as a result. Not exactly a recipe for getting maximal oxygen to the parts of the body (like the brain and heart) that really need it. This situation can be magnified negatively during exercise, when the body is under physical stress. Doing mountain climbers for intervals of sixty seconds or busting out some weighted squats requires some serious oxygen, which you may not be getting if you’re not able to make the most of your breath by breathing from the diaphragm.

There are a few ways one can learn how to breathe from the diaphragm, but one of the simplest ways is one that you can do anywhere, any time. Make sure you’re in a comfortable, relaxed position, but if you are seated, sit with proper posture (no slouching!). Place both hands gently on the stomach and take a few moments to breathe through the nose while focusing on expanding through your stomach and really letting the lungs fill. You should feel your belly rise quite a bit, while your shoulders and chest stay relaxed and rise only a little. Relax your stomach and exhale naturally, without forcing the air out. If lying down is an option you can advance this exercise. Maintain a comfortable position lying face-up with your feet on the ground and place a light but noticeable weight on your stomach (something like “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” or a similar weight is good), and work to breathe through the belly. This will help you properly recruit your diaphragm, although it may be a bit difficult, uncomfortable, and feel unnatural at first (“How to Activate Your Diaphragm,” Breaking Muscle).

Now for the important part: applying this to exercise. Of course, nothing worth having comes without a little work, and, in this case, maybe a little practice. Take a second, as often as you can, to think of your breath and do a self-check: am I breathing from my stomach, or am I really winded and starting to breath from my chest again? Simply having the conscious realization that you’ve stopped breathing from your belly is the first step to doing it more often. Remember, whether you’re on your last thirty seconds on the battle rope, doing heavy dumbbell rows, or swamped at work, taking a few deep breaths and letting it all hang out could be just what you needed to refocus and take on the task at hand.

-Maria Capuano